Author: Tasnim Alwa`l, @tasneemtatreez

This essay is authored by a guest contributor to The Tatreez Institute, and represents the author’s own research and writing. The author used AI-assisted tools to help translate this piece into English. Citation: Tasnim Alwa`l, “Stolen Threads: The Appropriation of Palestinian Embroidery by Israeli Designers,” The Tatreez Institute (blog), May 17, 2025.

When I first started practicing Palestinian embroidery, or tatreez in Arabic, during the ongoing genocide in Gaza, it was difficult to see its value amid the overwhelming atrocities. In the face of unimaginable suffering, embroidery felt small, almost powerless. What difference could preserving stitches and patterns make when lives were being destroyed? But the more I reflected on it, the more I realized that Palestinian heritage has always been an act of resistance. If our ancestors who witnessed al-Nakba held onto it, then there must be something deeply significant about its preservation.

This question led me on a journey of research and self-education. One of the most eye-opening sources I encountered was the Palestinian Heritage Encyclopedia, a book written in Arabic in 1981. In its final section, the encyclopedia detailed the many ways in which Israel has sought to appropriate and erase Palestinian culture. Among the most striking examples was the case of Ruth Dayan, who took famous Palestinian embroidered dresses and mischaracterized them as Israeli Fashion, even showcasing them at the White House. (Sarhan 1989). Because this history was not well documented, I had never encountered it before.

This discovery raised unsettling questions: How many other instances of cultural theft have gone unnoticed? How has Palestinian embroidery, once a symbol of identity and resilience, been transformed into an exotic aesthetic for Israeli designers? To answer these questions, I turned to three key case studies: Maskit Fashion House, Nili Lotan, and Rikma Fashion House. Each of these brands, in different ways, represents how Israeli designers have exploited Palestinian embroidery; first, through the labor of Palestinian embroiderers and later, through the erasure of their contributions altogether. Through these examples, I aim to explore the fine line between appropriation and outright theft of intangible cultural heritage, challenging the reader to rethink the normalizing narratives they have been told.

Ruth used charity visits like those to orphanages in Bethlehem as a means to gain access to Palestinian embroiderers and crafters for Maskit’s designs. Source: “Eulogy | The improbable friendships of Ruth Dayan,” The Forward, Mar. 2021.

Case Study I: Maskit Fashion House: Appropriation Disguised as Cultural Bridging

Ruth Dayan, the first wife of Moshe Dayan—the Israeli defense minister responsible for military campaigns during al-Nakba (1948) and al-Naksa (1967)—is often celebrated in Western media as a peace advocate who sought to bridge political and cultural divides between Arabs and Jews. However, her role in the erasure and appropriation of Palestinian heritage tells a different story.

In 1954, Dayan founded Maskit, Israel’s first fashion house, as a government-sponsored initiative meant to provide employment for newly arrived Jewish immigrants. While the brand was initially framed as a project to "preserve local craftsmanship," Maskit’s success was largely built on the labor of Palestinian, Bedouin, Druze, Lebanese, and Syrian artists and designers—many of whom were later omitted from its official history (Feitelberg, 2025).

After the 1967 al-Naksa, or the Six-Day War, Maskit expanded its workforce to include Arab designers and embroiderers, further integrating Palestinian embroidery techniques into its collections. Yet, while Palestinian hands embroidered the garments, the credit for these designs was claimed by Israeli designers, such as Fini Leitersdorf. This pattern of appropriation continued for decades, with Maskit borrowing heavily from Bethlehem and Gaza traditional dress styles, as well as Bedouin men’s attire, and they marketed them as "Israeli heritage" to Western audiences. Despite being praised as a mediator between Jews and Palestinians, Ruth Dayan's involvement with Maskit reveals a contradiction. While she promoted herself as a preserver of regional crafts, she actively benefited from the uncredited labor of Palestinian embroiderers in the following ways:

Maskit’s designs frequently incorporated Palestinian embroidery motifs, yet the culture nor the embroiderers were acknowledged.

The brand exhibited these designs internationally, presenting them as Israeli craftsmanship rather than Palestinian cultural heritage.

Dayan worked alongside elite Israeli designers—Fini Leitersdorf, and Sharon Tal—who modernized and commercialized Palestinian embroidery for Western luxury markets.

This raises a critical question: Can someone truly serve as a bridge between two cultures while simultaneously erasing one of them and obscuring the identities of the embroiderers whose work underpins their designs?

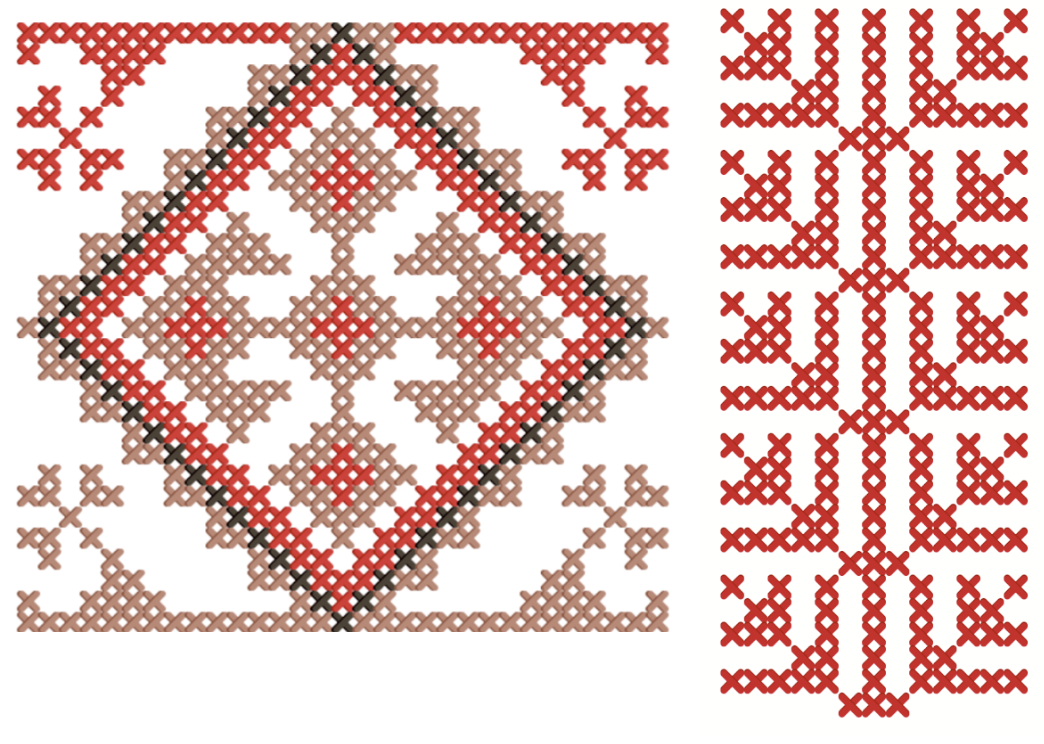

EXAMPLES: BETHLEHEM MALAK, GAZA THOBE, BEDOUIN MEN’S CLOTHING

1. The Bethlehem Malak Thobe

One of the most striking examples of appropriation is of the Malak Thobe from Bethlehem—a dress style from Bethlehem known for its elaborate couching embroidery and regal aesthetic. A 1970 Maskit photoshoot pamphlet clearly features a Bethlehem Malak Thobe with minimal alteration, yet the brand presented it as an Israeli garment (Oron, 1970/1980). Other examples include:

A 1970s Maskit dress found on eBay, which replaces traditional Palestinian fabrics with modern materials but retains Palestinian embroidery techniques, particularly tahriri embroidery.

Mini and maxi dresses incorporating small sections of Bethlehem chest panels—reducing intricate cultural motifs to decorative accents while stripping them of their meaning.

2. The Gaza Dress

Archival photos from Israeli museums reveal that Maskit repurposed elements of traditional Gaza embroidery into their designs. In one notable example, Maskit dresses included embroidery patterns that directly replicate old Gazan embroidery found in the chest panel of the traditional thobe.

3. Bedouin Men's Clothing

Maskit’s famous "Desert Coat", which remains central to its collections today, closely resembles traditional Bedouin men’s robes. A comparison between older Bedouin garments and modern Maskit coats shows undeniable similarities, yet the brand markets it as an "Israeli design" without reference to its Bedouin origins.

From International Showcases to Israeli Museums: Erasing Palestinian Heritage

While these Palestinian-inspired dresses are absent from Maskit’s current website, they are still circulating in vintage markets such as eBay, Etsy and other websites, labeled as "Vintage Israeli Maskit Dresses." This mislabeling creates a historical distortion, misleading non-Palestinians into believing these garments are part of an Israeli fashion legacy rather than Palestinian heritage. Furthermore, Israeli museums continue this cultural dispossession of Palestinians by honoring Ruth Dayan and her collections from the 1960s and 1970s, preserving them as "Maskit heritage" that documents the old-fashioned and heritage of Israel (Brown 2024).

Case Study II: Rikma Fashion House: The Appropriation of Palestinian Kufiya and Embroidery

Founded in the early 1960s in Tel Aviv, Rikma Fashion House was established by Rozi Ben-Yosef, a Bulgarian Jewish designer often credited in Israeli fashion history as the creator of Kufiya-inspired fashion. According to Israeli sources, Ben-Yosef was deeply "inspired" by Middle Eastern and Palestinian patterns, incorporating these motifs into her designs while stripping them of their cultural and historical significance.

Ben-Yosef’s work is an early example of Israeli designers adopting Palestinian symbols and textiles while rebranding them under a new identity—one that presents them as Israeli, modern, and fashion-forward, rather than belonging to the indigenous people of Palestine.

One of the most controversial aspects of Rikma’s work was its appropriation of the Kufiya (Keffiyeh), a garment deeply rooted in Palestinian resistance and identity. By the early 1960s, Ben-Yosef began incorporating the Kufiya fabric into her designs, particularly in dresses and caftans. This rebranding was not just about fashion; it was a political act, transforming a symbol of Palestinian heritage into a trendy, exoticized fabric for Israeli consumers.

The "Caftan" with Palestinian Elements: One of Rikma’s fashion photoshoots from the 1970s features a dress marketed as a “Middle Eastern-inspired caftan” but clearly incorporates a Beersheba chest panel with distinct embroidery traditionally worn and made by Palestinian women in the Naqab region.

Pink-Dyed Kufiya: Another significant example is the pink-dyed Kufiya fabric used in Rikma’s collections. While the traditional black-and-white Kufiya represents Palestinian nationalism, Rikma altered its color and incorporated it into Westernized silhouettes, diluting its political and cultural meaning (Ben-Horin, 2010).

The Hypocrisy and Theft in Presenting Cultural Garments

One of the most striking contradictions in Rozi Ben-Yosef’s legacy is how she framed her work differently depending on the audience.

To Israeli media, she positioned her designs as part of "Israel’s cultural heritage," aligning them with the Israeli melting pot and the diverse Hebrew tribes. This framing strategically erased the Palestinian and Arab origins of the textiles and embroidery she used, instead presenting them as an inherent part of Israel’s national identity (Ben-Horin, 2010).

To Western media, she took a completely different approach, describing herself as a "citizen of the world" who was simply curious to explore different design cultures. She framed her work as an appreciation of diverse craftsmanship, stating:

"Local and traditional crafts are the backbone of the design industry and have a strong social impact on our lives." (Ben Yossef, 2018)

In these statements, she positioned herself as a global designer rather than a cultural appropriator, avoiding any mention of how her work depended on Palestinian labor, motifs, and textiles that had been repackaged as Israeli. Yet, the irony remains—while she spoke of breaking boundaries and embracing regional influences, the reality was that Palestinian culture was being physically, politically, and historically erased under the Israeli occupation.

Palestinian artists and designers have been denied access to their own heritage through a combination of physical restrictions, cultural erasure, and economic exclusion. Military checkpoints, blockades, and displacement have cut many off from their ancestral villages and traditional craft spaces. Meanwhile, Israeli museums and designers rebrand Palestinian embroidery as Israeli heritage, erasing its origins and severing generational transmission. Younger Palestinian generations often struggle to access traditional techniques, such as the Mejdal fabric or specific regional embroidery styles, due to both displacement and the disappearance of local knowledge. At the same time, Palestinian symbols like the kufiya and thobe are freely commercialized by Israeli designers without acknowledgment, while Palestinians themselves are excluded from the same platforms or even punished for expressing their identity.

Case Study III. Nili Lotan: The Appropriation of Palestinian Heritage and the Contradictions of Her Image

Nili Lotan, an Israeli-born designer now based in New York, presents herself as an internationally-inspired creative force. However, her background as a former soldier in the Israeli Air Force, a military institution responsible for bombing Palestinian civilians, directly contradicts her curated image of peace and globalism (Swedenburg, 2007).

Despite her military past, Lotan has repeatedly drawn on Palestinian symbols of resistance and identity, such as the kufiya (keffiyeh) and Palestinian embroidery, incorporating them into her high-end fashion collections while stripping them of their historical and political significance. This dual role—one of an occupier and one of an appropriator—exposes the deep hypocrisy in how she markets herself and her designs.

One of the most striking examples of Lotan’s appropriation of Palestinian heritage was her Spring 2008 fashion line, where she transformed the iconic kufiya into designer dresses. The kufiya, a checkered scarf, is deeply associated with Palestinian identity, struggle, and resistance against Israeli occupation. Instead of acknowledging its significance, Lotan rebranded it as a fashion statement, disconnected from its roots. Lotan, who had served in the Israeli military, commodified a symbol of Palestinian resistance for Western consumers, a particularly offensive act given that Israeli policies systematically ban, criminalize, and stigmatize Palestinians for wearing the very same kufiya.

Palestinian Embroidery: Fascination Without Acknowledgment

On an Instagram post in February 2021, she wrote this caption: “In 2005, when I had just started my business, I wanted to incorporate authentic embroidery from Israel in one of my first collections. I reached out to the legendary Ruth Dayan, who in 1954 founded Maskit, with which she will always be associated. Maskit was a fashion house that incorporated the traditional techniques of Northern African and Yemenite jews with Western fashion.”

In 2006, she traveled with Ruth Dayan (founder of Maskit) to seek out Bedouin and Palestinian embroiderers. While she openly expressed admiration for Palestinian motifs, her statements reveal an unsettling detachment from their cultural and political significance: "Yemenite embroidery has one motif," explains Lotan, "while Palestinian embroidery is a whole world. Now I visit a group of women in Segev Shalom, near Be'er Sheva, for ideas. I also plan to use ideas from the sources that inspired Maskit, which I feel is a wonderful project." (Swedenburg, 2007)

She claimed that Palestinian embroidery "is a whole world", acknowledging its complexity, yet deliberately refused to credit it properly (Feitelberg, 2021). She incorporated Palestinian and Yemeni embroidery into her designs, but Profiting from them (Swedenburg, 2007). While mainstream media continues to frame Nili Lotan as a designer inspired by the Middle East region’s richness, her work often blurs and erases cultural lines.

In June 2021, The Times of India reported on the backlash faced by Israeli-American designer Nili Lotan for selling an embroidered cotton top labeled as “Palestinian,” priced at over 31,000 Indian Rupees and sold through luxury retailers like Nordstrom and Kirna Zabete. The embroidery on the blouse closely resembled cross-stitch motifs from the traditional Palestinian thobe, yet the designer’s website vaguely described it as:

“Light-blue embroidery pays tribute to Nili Lotan’s Middle East heritage.”

The article acknowledged the resemblance to Palestinian dress, but also highlighted the controversy: that an Israeli designer, with no cultural or historical ties to Middle Eastern or Palestinian identity, was profiting from a garment deeply connected to its people.

Amplifying the critique, fashion watchdog @diet_prada called out Lotan in June 2021 in a post where it provided a detailed response contextualizing the embroidery within Palestinian resistance. It reminded audiences that during the First Intifada, the thobe became a symbol of protest, with women incorporating national symbols into their embroidery after Israel banned the Palestinian flag. Diet Prada’s post drew a line between cultural inspiration and appropriation, exposing the hypocrisy of Israeli designers selling Palestinian resistance as a type of fashion, while Palestinians are criminalized for wearing it.

Screenshot from @diet_prada’s June 2021 post calling out Nili Lotan for using Palestinian embroidery in her designs without acknowledgment, highlighting the ongoing appropriation of Palestinian culture in the global fashion industry.

In addition to appropriating Palestinian embroidery in her early collections, Nili Lotan also drew on Yemeni embroidery, framing it as part of Israel’s “melting pot” through the inclusion of Yemeni Jewish heritage, again, without crediting the embroidery's cultural context or origin.

She was referring to the embroideries in Lotan's clothes as "No one would ever figure out where they came from. Even the outfit Paris Hilton wears was inspired by a Yemenite woman. I use these ideas in only a few of my clothes, but they give me a lot of pleasure." (Handwerker, 2006b)

Together, these examples illustrate how Lotan's designs are celebrated in global fashion media while obscuring the power dynamics behind the embroidery she adopts, a recurring pattern in settler-colonial fashion narratives. In addition to her appropriation of Palestinian and other cultural embroidery traditions, Nili Lotan frequently stages her photoshoots in occupied Palestinian areas, such as Mitzpe Ramon, Jaffa, and other historically Palestinian cities, further entrenching her brand in a landscape shaped by dispossession. Through these aesthetic choices, she romanticizes the geography of occupation while excluding its political realities.

Moreover, Lotan uses her Instagram platform to openly advocate for Israel. On November 7, 2023, she posted:

“My team and I gathered united for Israel in a rally for Israel to show our respect and solidarity.”

This public stance, paired with her use of Palestinian and regional crafts without attribution, exposes the deep contradiction at the core of her work, one that simultaneously profits from Palestinian cultural aesthetics while aligning herself with the entity, Israel, responsible for erasing them.

Conclusion: The Colonial Fetishization of Palestinian Craft

Through Maskit, Rikma, and Nili Lotan, we see a pattern of colonial appropriation—Israeli designers, originally from Russia, Bulgaria, Hungary, and the U.S., profiting from Palestinian heritage while erasing its origins. They market their work as "Israeli craftsmanship," yet their designs rely on Palestinian embroidery, Bedouin textiles, and traditional motifs.

Their hypocrisy is striking: they market themselves as artists and peacemakers while profiting from Palestinian embroidery, the kufiya, and Bedouin craftsmanship, art forms deeply tied to a people whose existence they refuse to acknowledge. Lotan, who once served in an air force that bombed Palestinian homes, now drapes models in kufiya dresses and speaks of being “bothered” by the conflict. Dayan, whose husband led military campaigns that killed thousands, built a fashion empire off the labor of Palestinian and Arab women, only for their work to be later sold as “Israeli heritage” and included in museums.

This is not appreciation, it is cultural theft that is rooted in the violence of erasure. When designers obscure the roots of the embroidery, kufiya, and thobes they use, they participate in a larger colonial project: the systematic erasure of Palestinian identity. Fashion, in their hands, becomes another tool of occupation.

Bibliography

Ben-Horin, Keren. “From Rags to Riches—Israeli Fashion Rediscovered.” On Pins and Needles, September 23, 2010. Accessed March 27, 2025. https://pinsndls.com/2010/09/23/from-rags-to-riches-israeli-fashion-rediscovered/.

Ben Yossef, Rozi. “Designers in the Middle.” Designers in the Middle, November 12, 2018. Accessed March 27, 2025. https://www.designersinthemiddle.com/nomadism/2018/11/12/rikma-by-rozi-ben-yossef.

Brown, Hannah. “MUZA Museum Highlights Middle Eastern Fashion in New Exhibit.” The Jerusalem Post, July 30, 2024. Accessed May 12, 2025. https://www.jpost.com/israel-news/culture/article-812403#google_vignette.

Feitelberg, Rosemary. “Ruth Dayan, Peace Activist and Maskit Fashion Founder Dies at 103.” Women’s Wear Daily, February 8, 2021. Accessed March 27, 2025. https://wwd.com/eye/people/peace-activist-maskit-fashion-founder-ruth-dayan-dies-at-1234726186/.

The Forward. “Eulogy | The Improbable Friendships of Ruth Dayan.” The Forward, March 1, 2021. Accessed March 27, 2025. https://forward.com/culture/465003/eulogy-the-improbable-friendships-of-ruth-dayan/.

Oron, Asher. Pamphlet 2 from the Maskit Catalogue – Fashion. Photography by Ben Lam. Issued by Maskit, 1970/1980. Naora Warszewski Archives. Accessed March 27, 2025. https://www.nli.org.il/en/archives/NNL_ARCHIVE_AL990049396580205171/NLI.

Sarhan, Nimir. Encyclopedia of Palestinian Folklore. 2nd ed. Vols. 1–3. Amman: Ministry of Culture, 1989.

Swedenburg, Ted. “Kufiyaspotting #22: Nili Lotan’s Kufiya Dresses on Fifth Avenue and at New York Fashion Week.” Swedenburg.blogspot.com, September 21, 2007. Accessed March 27, 2025. https://swedenburg.blogspot.com/2007/09/kufiyaspotting-22-kufiya-sheeth-in-silk.html.

Handwerker, Haim. 2006b. “Up In Arms - Israeli Culture.” Haaretz.Com, September 25, 2006. https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/culture/2006-09-26/ty-article/up-in-arms/0000017f-e0ca-d804-ad7f-f1face220000.

Lotan, Nili, "Grateful to be featured in @haaretz as one of the 50 most influential women in Israel," Instagram, February 6, 2021, https://www.instagram.com/p/CK7pWDaj2cp/

Lotan, Nili "My team and I gathered united for Israel in a rally for Israel to show our respect and solidarity." Instagram, November 7, 2023. https://www.instagram.com/reel/CzWm-E0L-F3/

TIMESOFINDIA.COM. 2021. “Israeli Fashion Designer Faces Flak for Palestinian Top.” The Times of India, June 10, 2021.https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/life-style/fashion/buzz/israeli-fashion-designer-faces-flak-for-palestinian-top/articleshow/83397072.cms

@diet_prada, “An Israeli designer profiting off Palestinian patterns with no credit,” Instagram, May 31, 2021, https://www.instagram.com/p/CP3Z3JPHG35/

Willem. 2017. “Jebel Sabir Embroidered Dresses (Yemen).” May 25, 2017. https://trc-leiden.nl/trc-needles/regional-traditions/middle-east-and-north-africa/pre-modern-middle-east-and-north-africa/jebel-sabir-embroidered-dresses-yemen.

Outnet, The. n.d. “NILI LOTAN Karine Embroidered Wool and Silk-blend Tunic | THE OUTNET.” THE OUTNET | Discount Designer Fashion Outlet - Deals up to 70% Off. https://www.theoutnet.com/en-pt/shop/product/nili-lotan/tops/3-quarter-sleeved-tops/karine-embroidered-wool-and-silk-blend-tunic/1647597315155801.

“Tirazain | طرازين.” n.d. Tirazain | طرازين. https://tirazain.com/archive/p/lily-f5j49-2ydlp-jkdr3-whrg5?rq=%D9%86%D9%81%D9%86%D9%88%D9%81.